Publisher:

Bonnie King

CONTACT:

Newsroom@Salem-news.com

Advertising:

Adsales@Salem-news.com

~Truth~

~Justice~

~Peace~

TJP

Nov-19-2009 02:10

TweetFollow @OregonNews

TweetFollow @OregonNews

Descartes' Disaster

Daniel Johnson Salem-News.comAll Science and no Spirit makes life sterile, meaningless and pathological. It's long past the time for Mankind to reclaim the essence of his humanity.

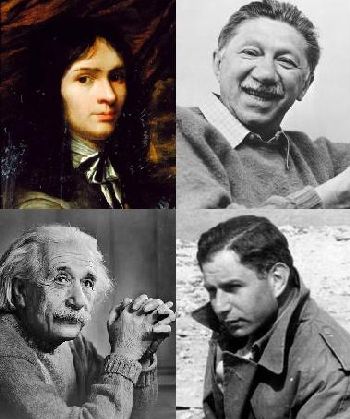

Clockwise from top left: French philosopher René Descartes, Abraham Maslow, founder of humanistic psychology, biologist Solly Zuckerman and Albert Einstein. Courtesy: quangkhoi.net, myartprints.com, wikimedia.org, rosettasister.files.wordpress.com, aamikeely.files.wordpress.com, digicoll.library.wisc.edu |

(CALGARY, Alberta) - Have you ever looked back on your life and thought how much different, better perhaps, it would be today if you had done A instead of B, or B instead of A? Can humankind do the equivalent? We can’t redo, but we can undo.

Before you can solve a problem, you must first understand it. When we look at the evolution of the human race, at the history of violence, warfare, and man’s inhumanity to man, there seems to be no pattern or a single thing onto which we can place our focus.

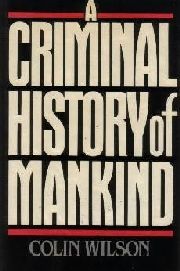

Colin Wilson, author of A Criminal History of Mankind suggests the problem is not what men do, but what they don’t do: “When we look back over the past eight thousand years, it is clear that the most irritating characteristic of human beings is their passivity. The mass of people accept whatever happens to them as cows accept the rain.”

But, says Columbia physicist Brian Greene: "At a deep level, there is a collective longing for an explanation of why there is a universe, how it came to take the form we witness, and for the rationale—the principle—that drives its evolution. The astounding thing is that humanity has now come to a point where a framework is emerging for answering some of these questions scientifically.”

The argument

My argument is simple and, in retrospect, obvious.

1. Before the beginning of modern science in the 17th century, people felt connected to the earth and the sky. Even if they couldn’t understand it or explain it; even if they were afraid of it; they knew intuitively that they were part of a greater whole.

2 René Descartes and the other founders of science reduced the world to what could be experienced with the five senses, disconnecting humanity from the whole and defining the universe as a clockwork machine.

3. Over the last three centuries, the science worldview has come to dominate our common culture, with the life of Spirit denigrated and denied. The result has been a world focused on material life and existence as if that is all there is. Nobel physicist Steven Weinberg sums up the modern nihilism of science today: “The reductionist world view is chilling and impersonal. It has to be accepted as it is, not because we like it, but because that is the way the world works.”

4. It’s no surprise that modern man is alienated, unhappy, and over-consuming to the point where the planet itself is under threat.

5. Let me be clear. I am not denying science; just denying it the role in society that used to be assumed by religion. As physicist Roger S. Jones says: "If anything, modern science incurs far less challenge and criticism than the church ever did. The church fathers would have given their eyeteeth to command for medieval Catholicism the kind of obedience and blind faith that we freely lavish on science today."

The birth of the universe

This is what cosmologists say they know.

Our universe appeared, apparently out of nothing, 13.7 billion years ago in what cosmologists call the Big Bang; an infinitesimally tiny fireball “exploded” and expanded to form the universe we know today. (In the Western biblical version, the world was also created out of nothing. The authors of other creation myths in antiquity had similar ideas.)

'Big Bang' Image: delamagente.files.wordpress.com |

The Big Bang model differs from them all by building on an apparently empirical base, implying elementary particle interactions in the early cosmos that are open to modern experimental verification.)

When the universe was about a thousandth of a trillionth of a trillionth of a trillionth (1 over 1 followed by 39 zeroes) of a second old, when its temperature was on the order of ten thousand trillion trillion (1 followed by 28 zeroes) degrees, the four forces of nature—-gravity, electromagnetism and the strong and weak nuclear forces—were a single force.

At this point the universe was inconceivably dense, inconceivably uniform and inconceivably tiny.

As it “cooled”, that single force separated into the four forces we know today—-gravity, electromagnetism and the strong and weak nuclear forces. Quarks combined into protons and neutrons, which then combined into atomic nuclei, then into atoms. After a few minutes only the simplest elements, hydrogen, helium and a small proportion of lithium, were created. That’s all there was.

Star children

As it expanded, the universe cooled to a temperature where atoms slowed sufficiently, so that gravity could become dominant and atoms could be mutually attracted, forming agglomerations of atoms. Over time, these clumps were gravitationally attracted to others to form increasingly larger clumps of matter.

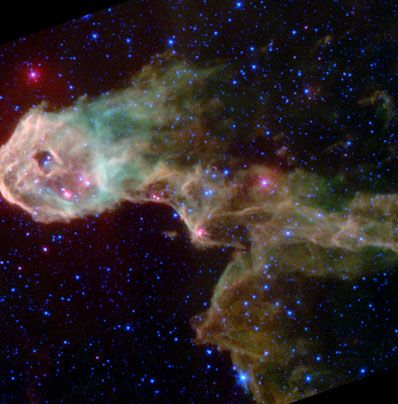

Protostars uncovered in multiple views of dark globule in IC1396. |

Some of the agglomerations of matter became so large that gravity pulled them together and the compression created heat. Think of pumping up a tire. As the pressure of the air in the tire increases, the air and tire become warmer. With proto-stars, the principle is the same, except that temperatures at the core of these bodies became sufficiently high to start nuclear reactions. The first stars in the universe were born.

As stars burned their basic fuel of hydrogen, heavier elements, up to and including iron, were created at the cores of stars. These heavier elements were created with higher temperatures and pressures in a process called nucleosynthesis. The successive nuclear fusion processes which occur within stars are known as hydrogen burning, helium burning, carbon burning, neon burning, oxygen burning and silicon burning. These processes create elements up to iron.

Here’s how other, heavier, elements are created.

The nucleus of an atom is made up of protons and neutrons, bound by the strong nuclear force. The protons and neutrons are composed of fundamental subatomic particles called quarks. The element an atom becomes is determined by the number of protons in the nucleus. Each proton carries a single positive charge.

Hydrogen is the simplest element with a nucleus of one positively charged proton and an outer shell of one negatively charged electron. Although it is the most abundant element in the Galaxy (ten times more abundant than helium, the next most widely occurring element), hydrogen makes up only about 0.14 percent of the Earth's crust by weight. It occurs, however, in vast quantities as part of the water in oceans, ice packs, rivers, and lakes. As part of innumerable carbon compounds, hydrogen is present in all animal and vegetable tissue as well as petroleum.

The elements of the periodic table are electrically neutral because the number of protons and electrons are the same and the electrical charges balance out. This is the atomic number of the element. For example, the atomic number for hydrogen is 1. For carbon, nitrogen and oxygen they are: 6, 7, and 8 respectively which is the number of protons in the nucleus of each of those elements.

As a star above a certain size ages, however, the hydrogen available for burning falls below a critical amount and the delicate balance of gravity causing compression, and nuclear burning forcing expansion, fails and the stars explode as novae and supernovae. It was in those explosions that the elements higher than iron were created (from the incredible heat and pressure of the explosions) and the elements were expelled into interstellar space. These newly created elements later coalesced, to form other bodies in the universe. All the elements in our bodies, the potassium, nitrogen, oxygen, iron—were created in the nuclear burning interiors. or explosions, of stars light years away, billions of years ago. We are children of the stars.

Where were we?

Courtesy: mydigitallife.co.za |

With his famous equation, E = mc^2 Albert Einstein showed that matter is frozen energy. If, as modern science argues, life is an extension of and merges from, matter, then it is reasonable to assume that we existed as potential life within that matter. Thus, we existed already in the Big Bang as future potential beings!

Two men are walking along. The first man asks: “Do you believe in life after death?”

“Yes,” says the second man.

Then the first man asks: “How do you know you’re not dead already?”

One evening a few years ago I was quite sick with a bad cough, chest congestion, etc. I had just finished dinner and started to cough. It was quite a violent cough when all of a sudden I couldn’t breath in—-or out—-something had become lodged in my windpipe. I tried harder and harder. I’ve had this happen two or three times before in my life but this time I couldn’t get an intake. The next thing I knew I was laying on my back with my eyes closed. Am I in bed? I wondered. I didn’t remember going to bed. I opened my eyes and looked up at the ceiling in the living room. An interesting aspect is that as I was trying to get a breath, I wasn’t scared or alarmed. I was just trying to recover my breath, as I have in the past.

I got up, none the worse for wear, not having hit my head on a table or chair. Leaning back in my chair a few minutes later, I reflected on the experience.

My first realization was: This is how people die sometimes, and I remembered hearing that Cass Elliot of the Mamas and the Papas had apparently choked to death on a ham sandwich. It turned out not to be true, but it does happen. I could easily have choked to death and that would have been that. As philosopher John Ralston Saul put it: “Most of us will likely drop dead on a subway platform, in the middle of an orgasm or straining on a toilet seat early in the morning. The real tragedy of death may be just how often it is comic.” For me, choking on a bit of detritus probably not much bigger than a tomato seed would have been comic indeed!

In the interval I was out of it, a few seconds, a minute or two, where was “I”? The same question applies, of course, to any time we are unconscious, which we routinely are for several hours each day—-ignoring dreams for this discussion.

I don’t know where I was except perhaps in the same place that I was over the last 13.7 billion years.

Photo: z.hubpages.com |

Death is euphemistically referred to in our society as a dreamless sleep. We put our pets “to sleep”. Death is timelessness. I could have been out of it for any length of time, a minute, an hour, a day, and coming to would have been the same except for physiological needs—after a day I might have had a sore back from lying on the floor for 24 hours or extreme bladder pressure. The experienced time difference between falling unconscious and waking up would have been of the same length—instantaneous. So it is with normal sleep, if we don’t dream or are unawakened through the night. We fall asleep, we wake up. That’s it. Nothing in between. When people ask how I have slept I sometimes say I don’t know—I wasn’t aware of being asleep. Consciousness is all.

Novelist Vladimir Nabokov described human life as “a brief crack of light between two eternities of darkness,” which brings up an interesting question: How long are these eternities? If we have eternal life, it stretches on ahead of us forever, an infinite number of hours, days or years—however we want to count them. But if we are not aware of them—before we are born or after we are dead, eternity is…nothing. It lasts no time at all. This is because consciousness defines time. No consciousness, no time.

Science writer Isaac Asimov once juxtaposed the two questions without realizing the implications of what he was saying: “I can only suppose that when I die, there will only be an eternity of nothingness to follow. After all, the Universe existed for 15 billion years before I was born and I (whatever 'I' may be) survived it all in nothingness.”

Enter René Descartes

The foundation of modern science was laid in the first half of the 17th century by the French philosopher René Descartes. There were others involved, like Francis Bacon, but Descartes was the key architect. Without his mathematical inventions, Isaac Newton could not have made his discoveries. That’s how important Descartes was in the establishment of modern science.

René Descartes Sketch: mathematica.ludibunda.ch |

Descartes’ had four rules for the study of the world:

- I Never accept anything as true which I do not know clearly to be true.

- Divide each of the difficulties under examination into as many parts as possible.

- Begin with the simplest and work upwards until reaching the most complex.

- Make enumerations so complete and reviews so general, that I might be assured that nothing is omitted.

From these four rules he built his famous proof that he existed (Cogito ergo sum—“I think, therefore, I am”). Like the Greeks a millennium before, Descartes believed the world to be a mathematical machine. He hoped to reveal the universal laws and discover all the secrets of a mechanical universe. The basis of modern scientific empiricism—empiricism as a theory of knowledge which asserts that knowledge arises only from sense experience—began with him.

Emotions and feelings had no place in Descartes’ philosophy or his life. He was more a thinking machine than a man. Others adopted that same attitude. Robert Boyle, one of the founders of the Royal Society, saw the universe as “a great piece of clockwork”.

Johannes Kepler whose Laws of Motion made Newton’s work possible said:

“My aim is to show that the celestial machine is to be likened not to a divine organism but rather to a clockwork. Might it not be possible, to show that the celestial machine is not so much a divine organism but rather a clockwork…inasmuch as all the variety of motions are carried out by means of a single very simple magnetic force of the body, just as in a clock all motions arise from a very simple weight.”

French philosopher Julien Offray de La Mettrie said:

“Let us conclude boldly then that man is a machine, and that there is only one substance, differently modified, in the whole world. What will all the weak reeds of divinity, metaphysic, and nonsense of the schools, avail against this firm and solid oak.”

That the world is entirely material, mechanical and only available through the senses is still the guiding philosophy of many, if not most, scientists today.

From this orientation comes metaphors about what the universe is.

In 1912, Edwin Tenney Brewster published Natural Wonders Every Child Should Know writing that:

“For of course the body is a machine. It is a vastly complex machine, many, many times more complicated than any machine ever made with hands; but still after all a machine. It has been likened to a steam engine. But that was before we knew as much about the way it works as we know now. It really is a gas engine; like the engine of an automobile, a motor boat or a flying machine.”

As technology advanced, so did the metaphors.

Physicist Robert Park today apparently believes: “We are electrochemical machines. The laws of motion, electromagnetism, thermodynamics, quantum mechanics, gravity govern everything. Our "emotions" are body chemistry changes governed by the brain .”

Harvard evolutionary psychologist Steven Pinker believes the same. In his book How the Mind Works (Hubris: as if he knows) he says:

“The payoff for the long discussion of mental computation and mental representation I have led you through is, I hope, an understanding of the complexity, subtlety, and flexibility that the human mind is capable of even ifit is nothing but a machine, nothing but the on-board computer of a robot made of tissue. We don’t need spirits or occult forces to explain intelligence.” He goes on to conclude that

“The mind is a neural computer, fitted by natural selection with combinatorial algorithms for causal and probabilistic reasoning about plants, animals, objects, and people. It is driven by goal states that served biological fitness in ancestral environments, such as food, sex, safety, parenthood, friendship, status, and knowledge.”

In the 1960s Edward Fredkin, then a professor at MIT and Konrad Zuse, who had constructed the first electronic digital computers in Germany in the early 1940s, jointly proposed that the entire universe was fundamentally a universal digital computer. “The idea,” says physicist Seth Lloyd today, “is an appealing one: digital systems are simple, yet able to reproduce behavior of any degree of complexity. In particular, computers whose architecture mimics the structure of space and time (so-called cellular automata) can efficiently reproduce the motions of classical particles and the interactions between them.”

Maslow’s Hammer

Science in our society is what I call an example of Maslow’s Hammer. Abraham Maslow, one of the founders of humanistic psychology, famously said: “When all you have is a hammer, you tend to treat everything as if it were a nail.”

Charles Darwin |

In 1869 Charles Darwin said to his lifelong friend Joseph Dalton Hooker that he would very much like to hear Handel’s Messiah again, but he was afraid to try it. “I dare say I should find my soul too dried up to appreciate it as in the old days; and then I should feel very flat.”

He said he felt like “a withered leaf for every subject except Science” and added: “It sometimes makes me hate Science, though God knows I ought to be thankful for such a perennial interest.”

His unhappiness over the loss of his former pleasures compounded over the years. He wrote in his Autobiography of the “curious and lamentable loss of the higher aesthetic tastes” and found that he “could not endure to read a line of poetry”, and felt that his mind had become “a kind of machine for grinding out general laws out of large collections of facts.”

"If I had to live my life again, I would have made a rule to read some poetry and listen to some music at least once every week.” If he had done that, he concluded, “Perhaps the parts of my brain now atrophied could thus have been kept active through use.” He explained that the loss of the taste for poetry was “a loss of happiness, and may possibly be injurious to the intellect and more probably to the moral character, by enfeebling the emotional part of our nature.”

Descartes had lived the same kind of life, except that he had intentionally rejected the emotional and feeling parts of life. For the next century or two, almost all art bowed to reason and attempted to become relevant by instructing rather than by giving pleasure. A clear, bare style without flourishes became the ideal. Novels were preferred to poetry for a novel could teach while poetry, said to John Locke, could only depict “pleasant pictures and agreeable visions.” Not until near the end of the eighteenth century did some begin to challenge the sterile Reason that Descartes had enthroned.

Echoing Darwin, behavioral psychologist B. F. Skinner, the most influential psychologist of the twentieth century, wrote in his autobiography that he felt very isolated and lonely at Hamilton College. “I remember walking the streets in physical pain from the lack of someone to put my arms around. Poetry may have helped.”

Nihilism

The end product of science can be nihilism, a denial of life.

Scientists do not consider themselves to be a part of the equations they invent and study. As ultra-Darwinist biologist Richard Dawkins (The God Delusion) puts it: "I believe that an orderly universe, one indifferent to human preoccupations, in which everything has an explanation even if we still have a long way to go before we find it, is a more beautiful, more wonderful place than a universe tricked out with capricious, ad hoc magic."

Biologist Peter Atkins: “As elaborate outcrops of the physical world, and no more than that, we are no more necessary to its existence than is a breeze.”

Steven Pinker: “Any explanation of how the mind works that alludes hopefully to some single master force or mind-bestowing elixir like 'culture', 'learning' or 'self-organization' begins to sound hollow, just not up to the demands of the pitiless universe.”

Richard Dawkins: “Much as we might wish to believe otherwise, universal love and the welfare of the species as a whole are concepts that simply do not make evolutionary sense.”

Even non-scientists have taken up the cause of nihilism. Historian Carl Becker: “Man is little more than a chance deposit on the surface of the world, carelessly thrown up between two ice ages by the same forces that rust iron and ripen corn.”

Sociologist Peter L. Berger: “History is a stream of blood, behind us, carrying us. Our age scoops up the blood in plastic bags and stores it, out of sight, for electronic retrieval. There is an obligation to remember, not in the memory cells of computers but in the heaviness of the heart. Over the memories of pain looms the solitary figure of the Virgin of Consolations, ever wiping the brows of the Quixotes of this world.”

Albert Einstein was predictably out of step, but his influence was minimal: “What is the meaning of human life, or, for that matter, of the life of any creature? To know an answer to this question means to be religious. You ask: Does it make any sense, then, to pose this question? I answer: the man who regards his own life and that of his fellow creatures as meaningless is not merely unhappy but hardly fit for life."

Einstein was an atheist and his references to religion were to the cosmic order he understood.

The Zuckerman box

In the late 1920s, biologist Solly Zuckerman studied the Hamadryas baboon in the London Zoo. He reported strong dominance hierarchies and high levels of aggression and fighting among the large baboons. Violence was frequent as well as widespread quarrelling. He reported that each baboon “seemed to live in perpetual fear lest another animal stronger than itself will inhibit its activities” and that any major disturbance caused the precarious social order to break down to “an anarchic mob, capable of orgies of wholesale carnage”. Later researchers studying these baboons in larger areas or in the wild found none of these things. As biologist Steven Rose said:

“The constraints of Zuckerman’s reductive approach had transformed the situation he wished to study and fundamentally misled him, even though his observations within that constrained situation were presumably perfectly accurate. Reductive methodology has served the simpler sciences of physics and chemistry well for three hundred years, and it is still the method of choice for most of the experimental work biologists do....But it may be failing us in our attempts to solve the more complex problems presented by the living world with which the biological sciences must now wrestle.”

Not referring to Zuckerman specifically, medical essayist Lewis Thomas observed:

“Is it not in the nature of complex social systems to go wrong, all by themselves, without external cause? Look at overpopulation. Look at [psychologist John B.] Calhoun’s famous model, those crowded colonies of rats and their malignant social pathology, all due to their own skewed behavior. Not at all, is my answer. All you have to do is find the meddler, in this case Professor Calhoun himself, and the system will put itself right. The trouble with those rats is not the innate tendency of crowded rats to go wrong, but the scientists who took them out of the world at large and put them into too small a box .” (emphasis added)

This last sentence cannot be emphasized strongly enough. As philosopher Arthur Koestler concluded, Zuckerman’s study revealed “the picture of a neurotic society labouring under abnormal stresses, whose members are bored and irritable, constantly bickering and fighting, obsessed by sex, and exposed to the rule of tyrannical, sometimes murderous, leaders. On the strength of this picture, one could only wonder how monkey societies in the wild survived at all.”

And so it is with mankind, except that it was René Descartes who put us in too small a box.

A bigger box

The opposite of science, as it is generally understood and practised, is holism, the understanding that All Is One.

Here’s what quantum physicists know.

There are no boundaries and everything in the universe is interconnected.

Albert Einstein’s great insight was that nothing in the universe can go faster than the speed of light. Physicists call this “locality”, as in, we live in a local universe. Yet consider a particle that decays into two photons and each flies off in an opposite direction. Because of their initial interaction, these two particles remain forever linked. Whatever happened to one particle would instantaneously affect the other particle, wherever in the universe it may be. Einstein called this “spooky action at a distance.” It has since been experimentally verified.

Their connection is called entanglement. This is because the two particles are not really two particles—they only appear that way to us. They remain forever aspects of the single original system. Quantum entanglement, says Cornell physicist N. David Mermin is “the closest thing we have to magic.”

Astronomer John Gribbin describes it this way.

“Virtually everything we see and touch and feel is made up of collections of particles that have been involved in interactions with other particles right back through time, to the Big Bang in which the universe as we know it came into being. The atoms in my body are made up of particles that once jostled in proximity in the cosmic fireball with particles that are now part of a distant star, and particles that form the body of some living creature on some distant, undiscovered planet. Indeed, the particles that make up my body once jostled in close proximity and interacted with the particles that now make up your body.”

Every potential particle in the universe was in the Big Bang, and was part of the original, primordial particle.

In life, says philosopher Alan Watts, “your soul, or rather your essential Self, is the whole cosmos as it is centered around the particular time, place, and activity called John Doe. Thus the soul is not in the body, but the body is in the soul, and the soul is the entire network of relationships and processes which make up your environment, and apart from which you are nothing.”

Psychoanalyst Carl Jung wrote in his memoir that "at times I feel as if I am spread out over the landscape and inside things, and am myself living in every tree, in the splashing of the waves, in the clouds and the animals that come and go, in the procession of the seasons." I used to have the same feeling when I was a child, but lost it. I think this applies to everyone.

Science rejects holism, only because it contradicts reductionism. Physicist Steven Weinberg declares that:

“At its nuttiest extreme are those with holistics in their heads, those whose reaction to reductionism takes the form of a belief in psychic energies, life forces that cannot be described in terms of the ordinary laws of inanimate nature. I would not try to answer these critics with a pep talk about the beauties of modern science. The reductionist world view is chilling and impersonal. It has to be accepted as it is, not because we like it, but because that is the way the world works.”

Here’s what cosmologists also say they know.

An international team of scientists has assembled one of |

There is something in the universe called dark matter. No one knows what it is but astronomers believe it makes up more than 90% of everything. It is detected only because of its gravitational effects on galaxies and groupings of galaxies.

Scientists accept this invisible, unknowable dark matter, but shy away from any possibility or consideration of spirituality and the paranormal even though it is something that many people know about intuitively.

We come back to metaphors. Consider astrology. What you read in newspapers and is popularized is totally unrelated to the original holism of astrology. Physicist Roger S. Jones says that,

"Much of the ridiculing and categorical rejection of astrology by modern scientists is because scientists have a kind of blind faith in the current metaphors of space and time and are ignorant of former ones....Our modern space—our metaphor of relationship—has been emptied of many of its relational characteristics. We no longer conceive of space as organic, hierarchical and participatory, nor as a realm of mind, knowledge and wisdom, as did our Greek and medieval forebears. We envision our space as empty, void—the absence of everything. If we believe that the Greek and medieval conceptions of space reflected the mental constructs and preconceptions of earlier minds, isn't it just possible that our modern empty and sterile space might likewise reflect our own preconceptions and beliefs?"

The original idea behind astrology was not to try to determine your fate by what planet or arbitrary pattern of stars were visible when you were born, but rather, to describe your place in the entire cosmos as it relates to you and your birth. Astronomer George Seielstad was not talking about astrology, but he described its operation. "Since everything is the product of its environment and since the environment is always changing, what an object is depends upon when it came into being." (his emphasis)

Conclusion, so far

There’s a saying: All work and no play, makes Jack a dull boy. In this context we can rewrite it as: All Science and no Spirit makes life sterile, meaningless and pathological. It’s long past the time for Mankind to reclaim the essence of his humanity, however it may look and whatever it may turn out to be.

==============================================

Daniel Johnson was born near the midpoint of the twentieth century in Calgary, Alberta. In his teens he knew he was going to be a writer, which is why he was one of only a handful of boys in his high school typing class—a skill he knew was going to be necessary. He defines himself as a social reformer, not a left winger, the latter being an ideological label which, he says, is why he is not an ideologue. From 1975 to 1981 he was reporter, photographer, then editor of the weekly Airdrie Echo. For more than ten years after that he worked with Peter C. Newman, Canada’s premier business writer (notably a series of books, The Canadian Establishment). Through this period Daniel also did some national radio and TV broadcasting. He gave up journalism in the early 1980s because he had no interest in being a hack writer for the mainstream media and became a software developer and programmer. He retired from computers in 2008 and is now back to doing what he loves—writing and trying to make the world a better place

Daniel Johnson was born near the midpoint of the twentieth century in Calgary, Alberta. In his teens he knew he was going to be a writer, which is why he was one of only a handful of boys in his high school typing class—a skill he knew was going to be necessary. He defines himself as a social reformer, not a left winger, the latter being an ideological label which, he says, is why he is not an ideologue. From 1975 to 1981 he was reporter, photographer, then editor of the weekly Airdrie Echo. For more than ten years after that he worked with Peter C. Newman, Canada’s premier business writer (notably a series of books, The Canadian Establishment). Through this period Daniel also did some national radio and TV broadcasting. He gave up journalism in the early 1980s because he had no interest in being a hack writer for the mainstream media and became a software developer and programmer. He retired from computers in 2008 and is now back to doing what he loves—writing and trying to make the world a better place

Articles for November 18, 2009 | Articles for November 19, 2009 | Articles for November 20, 2009

Salem-News.com:

Quick Links

DINING

Willamette UniversityGoudy Commons Cafe

Dine on the Queen

Willamette Queen Sternwheeler

MUST SEE SALEM

Oregon Capitol ToursCapitol History Gateway

Willamette River Ride

Willamette Queen Sternwheeler

Historic Home Tours:

Deepwood Museum

The Bush House

Gaiety Hollow Garden

AUCTIONS - APPRAISALS

Auction Masters & AppraisalsCONSTRUCTION SERVICES

Roofing and ContractingSheridan, Ore.

ONLINE SHOPPING

Special Occasion DressesAdvertise with Salem-News

Contact:AdSales@Salem-News.com

Terms of Service | Privacy Policy

All comments and messages are approved by people and self promotional links or unacceptable comments are denied.

Anonymous November 23, 2009 2:48 pm (Pacific time)

I really enjoyed your article. You (and other readers) may be interested in my recent blog-post entitled: "A False Choice: Reductionism or Dualism". It proposes complexity theory as offering a philosophical path that can embrace both science and spirituality. Here's the link:

http://jeremylent.wordpress.com/2009/11/18/a-false-choice-reductionism-or-dualism/

Hope you enjoy it.

Jeremy Lent

Thanks for your positive feedback, Jeremy. I'll check it out.

Henry Ruark November 21, 2009 9:50 am (Pacific time)

D.J. et al: Your statement re "But how can it be ...?" to response here seems certainly relevant to much, much more than simply physics. Hope you can follow that thread into whereveritmaylead, with runofcomments here as fine natural examination material !

Andrew Daw November 21, 2009 6:35 am (Pacific time)

The best article I've found on the internet anywhere, I say, Daniel. And to your: "All Science and no Spirit makes life sterile, meaningless and pathological." I would add "...and makes for a physics of part truths and theoretical error." So I hold that there is a precise date and place when and where physics lost its way. This was in October 1924 at the fifh Solvay Conference in Belgium. This was where the leading physicists of the day, including Einstein, Bohr, Heisenberg, Schrodinger, Pauli, Dirac and de Broglie presented papers and/or discussed the interpretation of quantum mechanics. The crucial outcome being that an indeterminate noncausal interpretion won the day and de Broglie's pilot wave theory was rejected outright.

The result was that the present standard model of quantum theory is based upon ineterminate and noncausal assumptions. And even though there is an alternative determinat and causal theory that has not been shown to be inconsistent with the results of a wide range of quantum experiments, and which is called Bohmian quantum mechanics, or the de Broglie-Bohm interpretation.

For longer than I care to remember, I have been attempting to develop an empirically justified account that may be decribed as a general theory of natural organisation. This account is intended to sufficiently justify and describe from its large scale observable effects as well as the results of quantum experiments, enough details of cause acting universally in addition to the known forces.

My blogs related to this theory are: towardsanageofcertainty.blogspot.com towardsanewageofreason.blogspirit.com

Thank you Andrew for your positive comments. You seem to be a person who knows something about this. I’ll check out your blogs.

Let's not forget that it was Feynman who said: “I think it is safe to say that no one understands quantum mechanics. Do not keep saying to yourself, if you can possibly avoid it, ‘But how can it be like that?’ because you will go ‘down the drain’ into a blind alley from which nobody has yet escaped. Nobody knows how it can be like that.”

I'm working on a Part 2, to which I look forward to your further comments and input.

Morna C-M November 19, 2009 9:24 pm (Pacific time)

Interesting. I'll hang onto this. Maybe post this page to Facebook, where others may see it. Thank you for writing it, and for sharing it.

Thanks for your positive comments. You're welcome to do that if you wish.

Ersun Warncke November 19, 2009 10:06 am (Pacific time)

Excellent article. It always strikes me, when I travel between urban areas and the wilderness, the extent to which "the world as a machine" only really makes sense if one surrounds themselves with an artificial machine-like world of their own creation. The world that moves according to scientific laws exists, but it is a small part of existence. The absence of truth, purpose, and morality within that world also tend to make its occupants a little insane.

Henry Ruark November 19, 2009 8:28 am (Pacific time)

Friend Dan: This is the best-yet; please keep 'em coming ! Beats any source yet found,and does S-N honor for publication. Agree with Winder re Darwin, esp."withered leaf" !

Winder November 19, 2009 7:39 am (Pacific time)

Very stimulating read. I particularly identified with the observations of Darwin on the things he gave up as he aged. I will strive to listen to more music, read some poetry and socialize more as I grow old...these are things I'd been foregoing, though not altogether intentionally. Thank you, Daniel, for that very wise advice, couched in a recap of conventional wisdom.

[Return to Top]©2025 Salem-News.com. All opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Salem-News.com.